Pages

▼

Saturday, February 23, 2013

Bathroom Monologue: Why People Get Sick In Winter

"Now scientists from the Empire said that it wasn't cold climates that made you catch disease. Even winters didn't actually care sickness with them, but rather since everyone headed indoors to escape the chill, they all shared their air, and diseases danced out of their mouths and mingled in the closed space. This was not Randy's opinion. He believed winter, with its mean-spirited cold and ice falling from the sky, convinced your unconscious to finally give up and send out distress messages to any neighboring diseases to help mercy kill itself. He founded this suspicion from honest introspection; not once had he trudged through ankle-deep snow and not found some part of him desire to blow his own brains out. The sniffles were part of that desire."

Friday, February 22, 2013

Bathroom Monologue: What Now Was Inland

They were half a generation beyond the end of oceans. Half a

generation since the elders had seen one, and half a generation since the young

could only imagine them. It was half a generation, down to the very day of

conception, when the tides of fermented blood rolled across ancient shores,

turning parched deserts to dripping beaches.

Upon this gory tide rode a ship. It flashed no bearing and

collided with a sandbar that, for half a generation, had been a popular hill.

It rose, and it shuddered, and they fled, and they sang warnings inland. Its

hull heaved for breath, and every groan of its sundry structures contributed to

the songs of the natives, until warnings turned to invitations.

There was not a soul aboard, nor a husk through which a soul

might have conducted seaworthy business. Yet there were many fine armors, which

the middling and young shared and donned, not for war, so much as for fashion

as only new varieties can afford. Beneath decks lay exquisite weapons, spears

that made the air bleed, and swords with epic poems etched along their edges,

verse honed to unparalleled sharpness. These, the natives beat into

ploughshares, and rapidly set about tilling and sowing before the gory tide

could dry up. Already it was fleeing into the horizon, as though happy to be

rid of the vessel.

They stripped, too, the skin of the ship, and fashioned it

into new bodies for their elders, so that Grandpars and Grandmars could join

them in the fields. They stripped the bones of the ship’s mighty underhauls,

which they fashioned into the outlines of new houses. When, at last, the ship

was naught but an empty indentation in a sandbar, every individual, young and

middling and elder, scooped up a handful to keep in memory. They pocketed their

handful of the ship as they set to work.

For this culture didn’t trust the ship had been a miracle.

If it were a miracle, then there would be two more, for miracles always come in

threes. One miracle is happenstance; two miracles a coincidence; three, a

confirmation. More, none alive had ever witnessed, and none dead had spun songs

about.

The uncertainty of miracles meant labor, raking the scabs

over the desert, tilling and churning, and planting the warts and rust from the

former hull, along with the thumb bones of their ancestors, which had been set

aside for just such an occasion. All this planting meant making music.

So they spun songs of who built the ship, who raised its

marvelous hide, who operated its great oars and gills, and every song of every

sailor was at the behest of a hero. They spun many songs about this hero’s

journey, about the madness that had driven him to jump overboard, or feed

himself to the ship so it might still live, or his pursuit of a love that had

launched a thousand such ships. None was particularly good, and none was

repeated, thus disqualifying them from truly being songs. If it’s only sung

once, a song might as well be an errant miracle.

They sang to work, which is the duty of song, to render long

labors brief, and render brevity pleasant. They erected fine homes of the

ship’s vast bones, and they patched every elder’s new body, and they marched

the rows of their uncanny crops in numbers only songs had ever referenced. It

could well have been the music that caused their crops to sprout.

They smelled the wrong rain coming. First a few seedling

squelched, and then rows belched brine. By noon their fields showered blood

upward, so many geysers as to terrify the elders. Their entire culture was

sprayed, and their entire world flooded by bounty. Sandbars disappeared beneath

viscous waves. The middling sang the young and elders into their new homes,

with solid ceilings, and the pores of their windows fastened shut, and their

rich floors rose. The riding tide lifted every home from its roots, settling

them to bob like corks in global liquor. Some elders fell into the maelstrom,

nerves feeble beneath their shells, yet their shells were as buoyant as the

hero’s ship had once been. It was the first opportunity in half a generation

that anyone had to drown, and not a soul took it.

Thursday, February 21, 2013

Bathroom Monologue: “Those who can’t do, teach.” -Anonymous

“I’ve never understood that phrase. William Shakespeare.

Niels Bohr. Bruce Lee. James D. Watson. Michael Faraday. Stephen King. Bill

Clinton. All of them teachers who were famous for work in their respective

fields.

“But beyond that: isn’t the music teacher who picks up a

cello and shows her pupil who to tune the strings doing? Doesn’t the very act

of her playing the music as example, and being able to bring others into

competence with the technical proficiency, demonstrate her ability to ‘do?’

“But beyond them: Jesus Christ was a teacher. He was, so

I’ve read, also God. If teachers can’t ‘do,’ and God is omnipotent, and ‘omnipotence’

is the ability to do anything to the utmost– isn’t there a grievous flaw in

someone’s claim?

“Since adolescence, ‘Those who can’t do, teach’ has struck

me as the refrain of the student who can’t do. Usually, it’s of the student who

can’t ‘do’ up to a teacher’s standards. You hate this authority figure, and so

they must fail at what they’re passionate about, not based on evidence, but

based on your disdain. Invention of someone else’s flaws to make ourselves feel

better is something we can all do.”

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

My Foot Stopped Working: What Chronic Pain Is Like

It strikes me that in some of my earlier neuropathy posts

that I’ve neglected to inform people about my basic health. You know that I’m

losing feel in my feet and legs, and sporadically lose the ability to move

parts of them. Perhaps you don’t know why the numbness was so immediately

apparent.

Since age 13, after some catastrophic medical malpractice, I’ve

been in constant pain in every part of my body. It’s been so long that I don’t

know how not hurting feels, except for this new alternative: not feeling

anything at all. The first time that my toes irrevocably went off the grid, I

was terribly frustrated. I’m used to navigating with them, and feeling the

twinges of pain in their second-from-last joints as the curl, the bellwethers

of how putting my foot down in each step will feel, and how sharp the pain will

be in my arch and ankle.

Perhaps the best analogy is to remember the last time you

had a really bad flu. That deep ache that settled on your flesh and in all your

tissues, that made every movement a deliberate labor and reminded you of all

those organs you take for granted. Sometimes one part, like my spinal column,

hamstrings or kidneys will ache worse, and the chief pain can even be a means

of focusing through the disorienting general pain. The worst is when the fog of pain is so great that I can no longer speak or compose full sentences. That general pain is so

distracting, because the reports come from so many parts of the body, that my

biggest daily problem can be thinking straight. This has been the last two decades

of my life.

It's a little tragic that I miss the pain in my feet. I'm too used to it. The human mind is a remarkably adaptive thing, and at present I'm wondering if I could eventually adapt to not feeling anything at all, perhaps over a course of decades.

Finally seeing the neurologist on Friday. It's been a long month of no leads or answers. Feeling a bit hopeful today.

Tuesday, February 19, 2013

Bathroom Monologue: 5 Failed Dating Tips from a Super-Rich Friend

- Approach

him with your eyes affixed to someone or something else nearby, then fake

tripping and spill your Merlot on him. Offer to buy him a new wardrobe.

That will work as a starter date.

- Ask

his position on prostitution and how it’s really just a contract between

consenting adults. Ask if he realizes marriage is a contract between

consenting adults. Finally, ask how much it should cost to marry him for a

while.

- Buy

every seat on the train, plane, theatre, or whatever else it is that you’re

at, I didn’t catch it at first. Anyway, when the two of you are alone in

the building, sidle up to him and act like this solitude must be kismet.

- Jesus,

I don’t know. Talk to him and see if you have chemistry.

- Hire some ex-military officers, preferably something professional, to attack him, and to take a dive when you run in to fend off their fascists. Keep their card for a second attack whenever your date loses steam.

Monday, February 18, 2013

Bathroom Monologue: Toothpick Man

Guy comes into town chewing a toothpick. It’s Sunday, so

everyone is at services, and he goes in, sits on the last pew. He doesn’t join

in the songs or prayers. He just stares forward and rolls the toothpick across

his molars.

The priest comes by to welcome him. The new guy ignores him

and chews his pick.

A couple of the socialites stop by to ask whose family he is

with. The new guy ignores them and chews his pick.

The town belligerent comes up and asks why he’s so quiet.

The new guy chews on that pick, and the town belligerent pokes him in the

chest, and the new guy chews some more. So the town belligerent grabs him by

the collar and thrusts him out of the church, out into the yard. He slaps the

pick out of his mouth and asks what he’s got to say about that.

Well the new guy reaches into his coat, produces a new

toothpick. He stares at the town belligerent, puts the pick in his mouth and

bites down with his canines.

The town belligerent jumps on his chest and starts beating

at the new guy’s nose, trying to pulp it. Some mildly superior Christians

eventually seize him by the elbows and haul him out of the yard.

Only a kid from the choir approaches the new guy. He brings

him a cup of water to dab the remains of his nose in if he wants. The new guy

doesn’t use the water, though. Instead he reaches inside his coat and fetches

two toothpicks. He chews upon one himself, and gives the other to the kid.

The kid holds the toothpick in front of his eyes, rolls it

between his fingers, studies it. It’s grainy wood, nothing special to his eyes.

So he asks, “What is this?”

So the new guy answers, “It’s an example of how to give your

characters distinction.”

Sunday, February 17, 2013

#NaNoReMo Update #3 – Almost Done

I’m nearly finished with Middlemarch,

and it feels like I’ve been cheating

in my 900-page climb. You see, my grandmother had a serious health issue and I

had to travel to Maryland

to help her. That meant taking four trains, two light rails, a cab, and

spending an additional six hours in lobbies. That also meant ample time to

digest chatty 1800s satire.

|

| She's doing much better, thank you. |

It’s funny reading satire when you’re being altruistic. 20th

century satire, and thus far, most of 21st century satire hinges on

a cynicism that all but denies the feelings that made me travel last week. Even

Evans/Eliot’s American contemporary, Mark Twain, would never have written a

fictional protagonist thinking or acting as I did, unless it was to mock

whatever petty foibles I exhibited along the way to good intentions. It reminds

that the scalpel is not the only instrument.

Middlemarch is

highly unusual satire, especially set against the modern strains. It’s not

invented to condemn an ideology, religion or social institution, but rather to

rigorously examine why its many characters screw up and hurt each other. Mr.

Bulstrode’s Protestantism is a moral barrier he’s constantly trying to

rationalize around in order to be selfish; Rosamond’s naivety corrodes her

life; Mr. Lydgate’s inability to politic constantly puts his public

works in jeopardy; both the couples of Mary and Fred, and of Dorothea and Will,

almost invent ways to not live happily ever after together because they

overthink and misread too often. She's beaten me to much of wanted to do in Literature by over a hundred years.

Because it’s gentler and not so obsessed with a singular evil, it’s easier for me to take seriously than 1984 or The Daily Show. And I enjoy The Daily Show, but Christ, everything Republicans do is the worst thing in human history. I’m still coming to terms with the phenomenon of comedy performed for applause instead of laughter. It feels like intellectual cancer.

Because it’s gentler and not so obsessed with a singular evil, it’s easier for me to take seriously than 1984 or The Daily Show. And I enjoy The Daily Show, but Christ, everything Republicans do is the worst thing in human history. I’m still coming to terms with the phenomenon of comedy performed for applause instead of laughter. It feels like intellectual cancer.

|

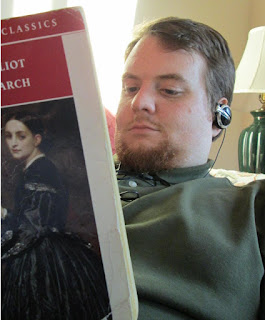

| Me and the world's largest copy of Middlemarch. |

Too much of modern satire is essential fictional polemic,

identifier an “other guy,” and painting them as dumb and/or evil, with only the

most minimal examinations of why. It shuts down your empathy towards this

“other” in favor of the pleasant outrages of having an enemy. As much as I

admired Catch-22 in my teens, this

ought to be the ground floor of satire, not the heavens.

Middlemarch brazenly scorns hypocrisy, misogyny, ignorance and dogma, but frequently does so with colossal inner working. It makes me wonder if I wouldn’t have preferred 1984 as a book from the perspective of an actual Big Brother on the rise and why he made his awful decisions.

Middlemarch brazenly scorns hypocrisy, misogyny, ignorance and dogma, but frequently does so with colossal inner working. It makes me wonder if I wouldn’t have preferred 1984 as a book from the perspective of an actual Big Brother on the rise and why he made his awful decisions.

It certainly makes me think about where satire could have developed

if Middlemarch had won. It’s not as

gratifying without the obvious audience pandering of modern satire, with

victim-heroes and strawman-villains. I can see why it lost. But I wonder if

this wouldn’t better serve the psyche, to constantly be reminded that every

potential for exterior failure exists within, as a means of progress towards

remedy.